I took the bus to work today because my car broke down, and I found myself in downtown Los Angeles, hemmed in on all sides by skyscrapers, alone with my bag and the headphones that covered my ears like an electric bulletin. Most artists milk the dusty landscapes of the open road or the same-same-sameness of a small town when they’re singing songs of lonely strangers or telling tales of getting up, getting out, and getting on. The National’s Matt Berninger, though, knows the feeling of being the barely-glowing light at the bottom of steel and glass canyons. The big city looks pretty until the neon starts to force itself upon you, and the glitter of bank signs and sky-high advertisements loses its luster once you’ve stepped through them enough. People in the city need a way out, too; no one’s safe; we hold onto the light by the edges and spin.

These are the assumptions that the National work from. These are the worlds, the people, the hearts that they create in their songs. Bruce Springsteen has always been (rightly) lauded for granting grace, vision, and dignity to America’s blue class, and for reminding the coasts that there’s something going on between them; Berninger’s stories draw similar lines around an entirely different class — the white, mid-20s/early-30s coastal hipster. At first, these groups seem to be diametrically opposed. The image of the self-conscious, faux-working class, gentrification-mad, spending-all-your-money-to-look-poor kids runs counter to that of the actual working class, those who already live in those parts of town and wear what they can afford. But Berninger recognizes the same things in the skinnyjeans that Springsteen sees in the bluecollars: a need to be reminded that life is too robust to be crammed entirely into workspaces and trapped between buildings, that there’s just as much dirt on Wall Street as there is in the fields. There’s much more to this, so look for it.

With all of the hype and laurels that accompanied Boxer, Berninger and the National found themselves at the tunnel end of other people’s points of view. May 20th saw the release of A Skin, A Night, French filmmaker Vincent Moon’s abstract portrait of the band that was filmed during the Boxer sessions. A Skin, A Night, which is available now on Beggar’s Banquet, is accompanied by Virginia, an EP of b-sides, live cuts, and covers (including Springsteen’s “Mansion on the Hill”) compiled in the wake of Boxer’s run.

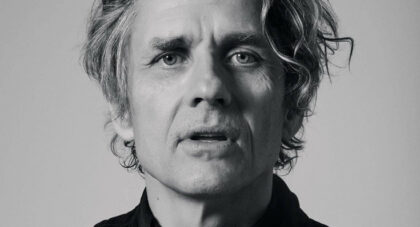

Aquarium Drunkard made it in out of the heat to ask Berninger a few questions about the stories he tells, as well as the story told about him and his band. words/marty garner

Aquarium Drunkard: How did you first get involved with Vincent Moon? Did he offer to film the Boxer sessions or did you guys approach him?

Matt Berninger: We've known him for about five years. He took all the photos for Alligator, the cover is his. He always has a camera with him so when he came to visit while we were working on Boxer he let it roll. He wasn't ever really planning to make a documentary.

AD: What do you guys think about A Skin, A Night? Is it strange watching yourself in the process of creation?

Matt Berninger: It's strange to see yourself doing anything on film. Especially a film that has been edited down to only show the uncomfortable moments.

AD: Your lyrics are a large part of what draws people to the National. Did you ever get a sense of being underappreciated as a writer back then, when the majority of people listening to your band didn’t speak the language that you were writing in?

Matt Berninger: I never used to think of myself as a writer. I always considered myself more of a sing-alonger until the lyrics started to get a lot of attention. Most of our early fans spoke French anyway so I didn't expect much.

AD: In watching A Skin, A Night, we get the sense that revision and sweat are very important to your band. Some artists (Neil Young, for instance) can write and record an album in a week, but the film makes it very clear that you worked incessantly on Boxer, tweaking melodies and lyrics on “Green Gloves” and “Slow Show” in particular. What is it that drives you to revise so ardently?

Matt Berninger: We just work and revise until we're happy with the song. We would all love for it to come quicker but we'll stay with it however long we need to.

AD: How do you know when a song is “finished”? Is it tempting to tinker a song to death? When listening to Virginia, for instance, it’s fascinating to know that the line “Everything you say has water under it” migrated from “Slow Show” to “Brainy.”

Matt Berninger: I stole that line from my wife Carin and kept trying to find the right place for it. I should have put that one in every song.

AD: At what point did you realize that Boxer was beginning to cohere into a unit? Did it come across in the editing and revising of the individual tracks? Did the formation of the album differ from that of Alligator?

Matt Berninger: We didn't really know what we were going to end up with until very near the end. I knew there were some great things happening but it was hard to see the whole picture from so far inside. Alligator was easier for some reason. I guess we had less to lose on that one.

Continue Reading After The Jump............

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.