There’s been a lot of talk recently about satire. What it is, what it does, if it really exists anymore. Following the Charlie Hebdo attack, the question whether or not the use of racist imagery can ever be sufficiently ironic has been a noticeably polarizing one. Everyone poring over the nuances of a French, left-leaning magazine (and, yes, its oftentimes crude appropriation of racial stereotypes) has also opened a larger debate, however. Not only in regards to free speech and political correctness, but also when it comes to satire per se.

In the wake of recent events, the writer Will Self found reason to draw a line in the sand:

‘[T]he test I apply to something to see whether it truly is satire derives from HL Mencken's definition of good journalism: it should "afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.” The trouble with a lot of so-called "satire" directed against religiously-motivated extremists is that it's not clear who it's afflicting, or who it's comforting.’

Leaving aside the irony of any good, moral definition having sprung from the mind of an unapologetic elitist-racist like Mr Menken, let’s think about this use of affliction as a moral barometer. (Let’s also gloss over the fact the Menken-Self test becomes rather less precise where groups wrangle over who is the more afflicted and who is being afflicted by whom.) The thesis here is that we should seek to protect the underdog, the lumpen few–which is no bad thing, obviously. Satire is surely meant for the bad guys, for taking down the complacent powers-that-be. However, according to Self, if satire is to maintain its moral backbone–if it is to be ‘good’–it can only do so by punching upwards and away from the have-nots. In other words, satire’s shit sandwich should be left for the status quo alone. Thou shalt not mock the underprivileged, the put upon, the uncomfortable…

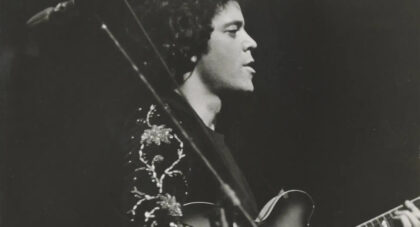

My rather more succinct definition of ‘good’ satire is Randy Newman. Others may throw around more technical, more literary names (Juvenal and Horace, the Minippean, the Hogarthean), but I prefer Newman’s name because of what it represents in regards to the art of satire. Show me any recent think piece about what good satire is or is meant to be and my response is invariably going to be Well, what about Randy Newman? And that’s because, when we talk about Newman’s satirical songwriting, we are necessarily talking about more than straight mockery and poking fun. This is about making you feel something alongside the laughter. It’s about stripping away pretense in less-than-obvious ways and making you swallow hard facts. More importantly, it’s about never being made comfortable.

Let’s get Newman’s best known song, "Short People", out of the way first, as it both is and isn’t the kind of exemplary Randy Newman satire I want to discuss. It was such a staple of the late-Seventies (kept out of Billboard’s number one spot by no less than "Staying Alive") that very little recap is needed. Suffice it to say, the song’s narrator has a thing against short people. What we are offered in the lyrics is a laundry list of grievances, all the result of short people with their ‘grubby little fingers’ and ‘nasty little teeth’. So, at first glance anyway, this would seem like comedy very much at the expense of the little man. (The song pushed enough buttons to get legislation drafted in Maryland to keep it off the airwaves). Admittedly not quite as sophisticated as Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal, the irony was still lost on some listeners. On the face of it, these lyrics are offensive, aren’t they? Don’t short people have a hard enough time without a bouncy song poking fun at their shortcomings? What was frequently missed was the characteristic double-ness of Newman’s satire. The laughable stupidity of the song’s prejudice is the un-laughable stupidity inherent in all prejudice. Once that central irony is appreciated, we can see that the target isn’t demonic little people, it is our own prejudicial stupidity. The butt of the joke is all of us.

As Newman himself has explained in a number of interviews, it’s too easy to say ‘prejudice is bad’ and have done with the issue. ‘I find it more natural to do it in an indirect way by having a character who states the case. I always think the audience is a little brighter than some of the people in my songs.’

That sense of the indirect route, of Newman-ian Double-ness, is a fundamental to his satirical songs. In "Davy the Fat Boy" we find a carnival barker who exploits the rotundity of an orphaned ‘friend’ for monetary gain. Drawn into the sideshow, listeners are held to account. Again the finger points at us (‘I think we can persuade him to do/The famous fat boy dance for you.’) Another great example is what might be considered Newman’s first satirical masterpiece–"Sail Away." There too we find a huckster disguising cruelty underneath a sheen of philanthropy and communal spirit: ‘In America, you get food to eat/Won’t have to run through the jungle and scuff up your feet/You’ll just sing about Jesus and drink wine all day/You all gonna be an American.’ You want irony? Well, imagine a slave trader backed by a string arrangement as sweepingly gorgeous as anything by Aaron Copland. Imagine him laying down a piano figure filled with the ghosts of Stephen Forster and Hoagy Carmichael and singing the praises of ‘the sweet watermelon and the buckwheat cake.’ It is unsettling, almost painful, the way the song balances a slave trader’s reassurances (‘In America every man is free’) with something musically so beautiful that it makes us want to get on the boat. And all this despite Newman’s treading very sensitive ground indeed (‘climb aboard little wog, sail away with me’). We know this history, we know the suffering it was predicated upon and how it turned out. But the song works as great satire because it doesn’t let us off the hook so easily.

We don’t laugh at this style of irony and find our moral superiority still intact. The funniness gives way to darker truths. Try listening to "Rednecks", for example (the epitome of an ironic Newman-esque one-two punch) and remain sitting comfortably. You might even laugh with relief at the first couple verses and the pot-shots taken at the ‘good ol’ boys from Tennessee,’ but come the final chorus, Newman makes sure the irony is pointed squarely at you.

Religion isn’t off limits for Newman, either–but you have to be mindful of the way his brand of satire deals with this subject matter, particularly in "God’s Song (That’s Why I Love Mankind)", the song that closes-out the Sail Away (1972) album.

By this point in the album, we’ve already heard an unadulterated song of praise (‘He Gives Us All His Love’) and a bleak, atheistic lament (‘Old Man’), but ‘God’s Song’ shuts the door on unquestioning faith and shuts it hard. Satirical to its core, it is also serves up one of Newman’s darkest ironies–and does so in no less a voice than that of god Himself. The song’s subtitle hints knowingly at Threepenny Opera’s ‘What Keeps Mankind Alive?’ but what we get musically-speaking is closer to "St James Infirmary Blues": just solo piano and voice, along with a faintly tapping foot reminiscent of John Lee Hooker. On the face of it, it’s a bluesy dirge sounding the death knell for the very concept of a compassionate God. A theodicy to end all theodicies. If Dylan rooted his Americana in the story Abraham and Isaac, Newman now pushes it even further back, to the first murder, the first conscious act of violence and cruelty.

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.