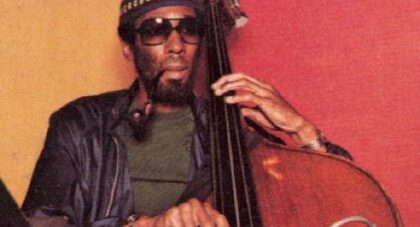

47 years after its original release and resounding commercial failure, the Hampton Grease Band's Music To Eat stands as a crucial entry in the experimental American music canon. Roaring out of Atlanta in the late '60s, HGB was led by quixotic vocalist Col. Bruce Hampton, alongside guitarists Glenn Phillips and Harold Kelling, and the rhythm section of bassist Mike Holbrook and drummer Jerry Fields. Though the poly-genre avant-garde sounds of Captain Beefheart or Frank Zappa serve as apt comparisons, the Grease Band was its own thing, blending jazz, blues, rock, with inscrutable and demented cut-up poetry. Though the band never recorded a follow-up, Music To Eat would go on to cult status, inspiring nascent punks and the burgeoning jam band scene of the 1990s, of which Hampton was a figurehead with his Aquarium Rescue Unit outfit, which shared stages with Phish, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, and Widespread Panic.

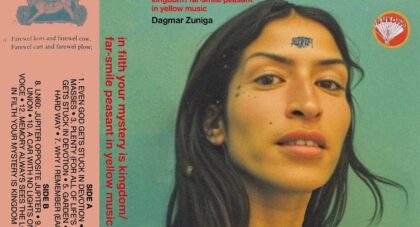

Recently, Real Gone Music reissued the record on "Georgia Peach" colored vinyl, dedicating the release to Hampton, who passed away in 2017 after collapsing on stage. Guitarist Glenn Phillips, whose solo discography is vast and picks up the thread first tied by Hampton Grease Band, joined Aquarium Drunkard to discuss the record's baffling genesis and legacy. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and cohesion.

Aquarium Drunkard: It's taken some time for Music to Eat to get its due, but at this point, it’s a cult classic. The oft-repeated story is that it was at one point one of the worst selling records in the Columbia catalog. Were you ever able to verify that?

Glenn Phillips: There were a lot of complications when it came out. Business-wise, the way things were with the band and management. The way the deal was structured [was] through [record man] Phil Walden, who inserted himself into the middle of the deal and got a great deal of money and very little of it filtered down to the band. Columbia had put forth a lot of money to him to promote the record, which Phil wasn’t legally obligated to do. So Columbia felt kind of burned by the deal. They felt they had already put the money out to market it and they didn’t want to have to do it again. So the record didn’t get much marketing when it came out. The people at Columbia did not know what they were dealing with. The music was very eccentric, very in its own world, and they were literally marketing that record as a comedy album. They labeled it "comedy" and it was getting filed alongside Don Rickles and Bill Cosby, you know in the comedy [sections of record stores]. So what we were told at the time was, and this was just that time, we were told that it was the second worst-selling Columbia record, second only to a yoga record. And that may very well be true, that's what we were told at the time. Now here we are in 2018, and that story has gotten repeated a lot. I don’t think that’s probably true at this point in time.

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.