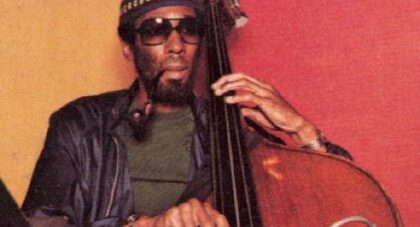

Jaimie Branch has been playing the trumpet since the age of nine, working the possibilities of her instrument to recreate the music that lives in her head. Her latest album Fly Or Die II: Bird Dogs of Paradise delivers challenge and experiment in the context of irresistible swing . . .

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.