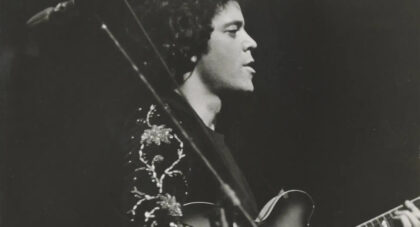

When asked what he’s most proud of in his five decade career in music, the answer doesn’t come easy for Makoto Kubota. The prolific Kyoto-born singer, songwriter, and producer has never been one to look back at his past work, and like his longtime friend and collaborator Haruomi Hosono, Kubota remains eternally humble, preferring to let the music do the talking. Until now.

We had a long, wide-ranging conversation with Kubota, lasting until the wee hours of the morning. Below are excerpts from the four hour chat—one of very few interviews with Kubota that has . . .

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.