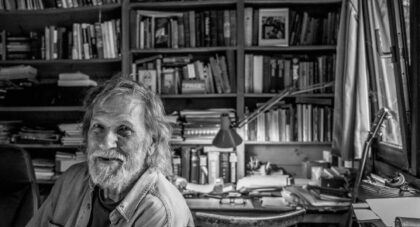

In the late 1980s, after a split with his Spacemen 3 partner, Peter Kember, Jason Pierce set out to make a new kind of music, less guitar-driven, more orchestral, founded on hauntingly simple melodies, but blown out with lush arrangements, blistering noise and free-wheeling instrumental improvisation.

This year, Fat Possum has begun reissuing the first four Spiritualized albums on vinyl. We talked to Pierce about his extraordinary 1990s run, his creative process, his influences and the way that music, when done well, can transport you into different times and different places . . .

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.